Increasing Social and Spatial Inequalities in Parental Co-Residence

Blog post: Amber Howard

Full paper authorship: Cody Hochstenbach, Amber Howard and Rowan Arundel

In recent decades, housing systems in many countries have moved away from policies that constrain market forces toward those that encourage them. This has found form in the promotion of private homeownership, the deregulation of rental markets, and the scaling back of social rental options, leaving individuals largely responsible for meeting their own needs. At the same time, living costs continue to rise faster than wages, and young adults in particular struggle to secure a place to live.

The family has become a critical unit for housing provision in this context, with generations increasingly coming together to overcome challenges to access. This finds form not only in direct intergenerational financial support, as has been well documented, but also in a growing reliance on the parental home. Indeed, across high income countries the share of young adults living in the parental home has increased in recent years, following decades of decline.

However, spatial context, such as local housing market affordability, and the availability of individual and family resources are important factors determining the need and the possibilities to co-reside. Drawing on data from the early 2000s, our research examines the socio-economic and geographic stratification of parental co-residence among 25–34-year-olds in the Netherlands.

Spatial patterns of co-residence

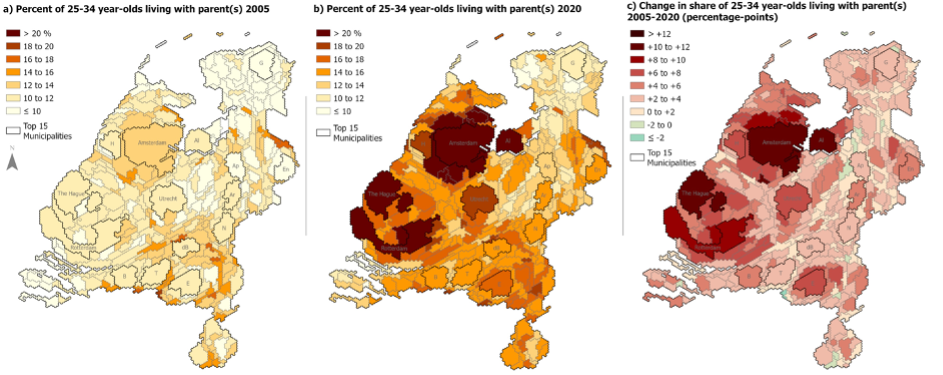

Our research found that parental co-residence has increased across much of the Netherlands, with the most striking rises observed in the Randstad region—the economic heart of the country that is home to its largest cities as well as several university towns. This is where housing costs are highest, yet job and education opportunities are concentrated.

We found that while co-residence has risen most sharply within the major cities, this has been closely followed by the suburban municipalities surrounding them. In the case of Almere—a satellite city east of Amsterdam— increases in co-residence were even steeper than in the capital. This might imply that young adults are increasingly unable to settle in these urban centres due to particularly high housing costs, and make use of family homes in relatively commutable distance.

Figure 1: Spatial distribution of co-residence in the Netherlands in 2005 (a), 2020 (b), and changes overtime (c) (%)

Data source: Statistics Netherlands System of Social-statistical Database (SSD).

Notes: Map is distorted based on population of municipalities using Gastner/Newman algorithm (Gaster & Newman 2004). Municipality abbreviations: Al = Almere, Ap = Apeldoorn, Ar = Arnhem, B = Breda, dB = den Bosch, E = Eindhoven, En = Enschede, G = Groningen, H = Haarlem, N = Nijmegen, T = Tilburg

Socio-economic patterns of co-residence

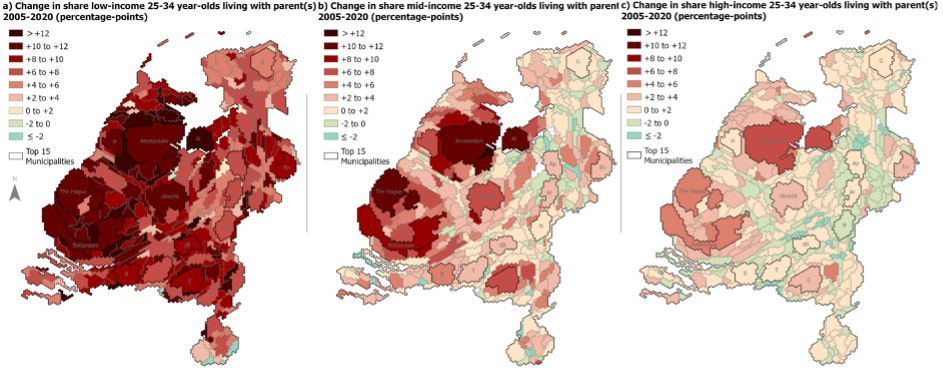

Distinct patterns emerge when breaking down these geographical analyses by income. We found that low-income young adults have seen very strong increases in co-residence within the major cities but even more notably in many adjacent municipalities. Among middle income groups, the strongest increases are still seen in the major cities. Among higher-income young adults, rates of co-residence have risen slightly in and around major cities and particularly the capital, but increases are far less pronounced compared to their low- and middle-income peers.

When we consider trends in the North, East and South of the country where housing market pressures are not as intense, the increase in co-residence has been much higher and wider spread among lower-earners, suggesting these groups face increased challenges in achieving residential independence even in more affordable areas. High- and even middle income groups are better positioned to afford independent living in less pressurised housing markets outside of the Randstad region, with rates of co-residence even decreasing in some areas.

In short, our findings imply that for higher-income groups, living with parents is often a choice rather than a necessity driven by housing constraints, which have particular salience for low- and increasingly middle-income young adults.

Figure 2: Changes in spatial distribution of co-residence in the Netherlands 2005-2020 (%-point) by low- (a), middle- (b) and high- (c) income group

Data source: Statistics Netherlands System of Social-statistical Database (SSD).

Notes: Map is distorted based on population of municipalities using Gastner/Newman algorithm (Gaster & Newman 2004). Municipality abbreviations: Al = Almere, Ap = Apeldoorn, Ar = Arnhem, B = Breda, dB = den Bosch, E = Eindhoven, En = Enschede, G = Groningen, H = Haarlem, N = Nijmegen, T = Tilburg

Implications of socially and spatially uneven trends in co-residence

The findings of our study raise concerns over growing inequalities in access to urban opportunities. They suggest that education and labour market opportunities may be increasingly accrued to those who can afford urban migration, or who have parents with housing in convenient city locations and the space and resources needed to host them into adulthood. Contrarily, those without these privileges might increasingly struggle to realise the benefits of urban living, impeding social mobility and entrenching social and spatial inequalities between generations.

Alongside the challenges faced on an individual level, the findings of our study also illuminate possible implications for cities. As high-priced urban areas risk becoming enclaves for the affluent as lower-income young adults are priced out, we anticipate an intensification of gentrification processes as class-based exclusions have amplified.

Takeaways from the study

To sum up, the findings of our study point to increasing socio-spatial inequalities in co-residence. They challenge media narratives around young adults living with their parents which portray them as “kidults” and frame their delayed independence as a “failure to launch”. Rather, they highlight how structural factors—including localised housing market pressures—are fundamentally reshaping opportunities for residential independence. Such pressures drive increasing barriers between better-resourced young adults with conveniently located urban parents, and those without.