Following the ESRC Festival of Social Science event ‘Youth Unemployment: Debating Solutions for the Future’ on the 10 of November in Sheffield, Chris Devany summarises the discussions that took place around (un)employment, mental health, and welfare stigmatization.

The speakers at the event were:

- Nigel Brewster, Vice Chair of the Sheffield City Region (SCR) Local Enterprise Partnership and Founding Partner at Brewster Pratap Recruitment Group.

- Sadie Charlton, Talent Match Wellbeing Coach at a youth charity in Sheffield.

- Dr Richard Crisp, Reader at the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research (CRESR) at Sheffield Hallam University

- Chris Devany, PhD student in CRESR at Sheffield Hallam University.

‘There are no unemployed people’

There is now a prevailing view among many in positions of power within the UK that we now have close to ‘full employment’ just one short decade on from the tumultuous financial crisis. Clearly, the labour market has improved significantly since the dark days of 2009/10, yet the issue of youth unemployment is still present. For young people the spectre of unemployment looms large over many cities and towns in the UK – especially in those areas most affected by rapid deindustrialisation.

Upon this backdrop I wanted to organise an event which brings together researchers, youth workers, local government, and businesses to discuss the issue of youth unemployment and explore ways to support young people. In helping me achieve this I am thankful to Richard Crisp (CRESR), Nigel Brewster (Brewster Pratap), Sadie Charlton (youth charity in Sheffield), my co-organiser Abigail Woodward and the attendees for taking the time to contribute.

Youth (Un) Employment – The Present State of Play

(Richard Crisp and Nigel Brewster)

The idea that young people in late capitalist societies face significant challenges in comparison to their older peers is one that is broadly accepted across the spectrum. Youth transitions have become increasingly complex, linked to a fractured labour market that no longer provides the rapid entry to employment it did in the past (Furlong and Cartmel, 2007; MacDonald and Shildrick, 2007; McDowell, 2002; 2011).

The factors that influence modern youth transitions are many and complex, including – the expansion of Further and Higher Education, declining heavy industry, rising housing costs, geography, social class and changes to the welfare state. Furthermore, it is the younger cohort who face the greatest challenge in terms or entering/re-entering the labour market during recessions. In such contexts, youth unemployment rates tend to increase substantially relative to those of the overall population, due in part to a lack of experience in relation to their older peers and the cost of training (Bell and Blanchflower, 2011).

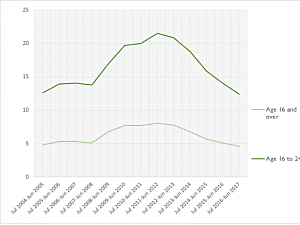

Unemployment Rate (2004 to 2017)

(Richard Crisp and Nigel Brewster)

Statistics relating to youth unemployment show that the labour market has been moderately successful in creating roles for younger people (particularly in comparison to some other EU countries). Official youth unemployment (16-24) in the UK is currently at 12%, significantly below countries including Sweden (17.4%), Belgium (21.6%) and France (23%) (House of Commons, 2017). However, scratching beneath the headline figures suggests that precarity in low paid employment for young people is a significant challenge. Use of Zero Hours Contracts (ZHCs) (employment contracts that do not guarantee a minimum number of hours) as businesses react to uncertain demand and stagnant productivity has increased from 100,000 in 2004 to 880,000 in 2017, with young people among the groups most likely to be on ZHCs (ONS, 2017). The lack of certainty for young people in work can adversely impact on their quality of life as they struggle to get by in light of low pay, insecure employment, reduced access to welfare as well as escalating costs of food, transport and housing (Unwin, 2016).

Despite these challenges, the notion that some young people do not want to work was wholeheartedly dismissed by all the speakers – at no point in their careers had they encountered any young people who were content to be outside of the labour market.

The Changing Welfare State – Sanctions, Conditionality and Stigmatization

(Richard Crisp and Chris Devany)

From a policy perspective youth unemployment is shown to be discursively framed through the narrow lens of ‘supply-side orthodoxy’, that sees worklessness and poor employability as the result of low skills, cultural shortcomings and low aspirations. This deficit model is, however, inadequate in fully explaining youth unemployment. The current cohort of young people in the UK possess more qualifications than ever before, thus youth unemployment cannot be wholly addressed through the ‘skills agenda’. A more nuanced discursive approach is needed which considers the structural distribution of youth unemployment (Crisp and Powell, 2016; Beatty and Fothergill, 2016).

The discourse of employability, supply-side orthodoxy and the deficit model approach to youth unemployment since the financial crisis of 2008 has legitimised an increasingly punitive regime of welfare conditionality and sanctions, which act to distance young people from the support once offered by the welfare state. During times of high youth unemployment governments have historically implemented ‘relief cycles’ where ‘conditionality is largely intensified during periods of economic growth and eased during downturns’ (Crisp and Powell 2016; 1787). During the recent spike in youth unemployment the opposite approach was pursued in the UK – as rates of unemployment increased among young people the coalition and Conservative governments made it increasingly more difficult for young people to access, and stay within the welfare system. Measures included mandatory ‘back to work’ training schemes, weekly ‘signing-on’ at Jobcentre Plus (JCP), and reducing the amount paid for Jobseekers Allowance the newly implemented ‘Youth Obligation’.

Against the backdrop of an increasingly punitive welfare system, attention to different measures of unemployment suggests that significant numbers of young people are choosing to disengage with the benefits system. The number of 16-24 year olds claiming welfare has dropped by 61% since 2003, faster than the fall seen for the 25-49 age group (NOMIS, 2017a). Furthermore, the current 16-24 claimant count (164,690) is far below the unemployment count for this age group of 542,600 and the NEET count (not in employment, education or training with no time stipulations) of 661,000 (NOMIS, 2017a). These wide differentials strongly suggest that large numbers of young people are living without income from welfare or employment.

Why are many young people not claiming benefits that they are entitled to?

(Chris Devany)

My ongoing doctoral research with a small sample of young people begins to answer this question. At the time of the event, I had conducted 24 qualitative interviews with young men (18-25) and 24 interviews with stakeholders exploring the lives and coping mechanisms of hidden NEETs (those not in employment, education or training whist not claiming welfare). Recruiting hidden NEETs for qualitative research was a considerable challenge and involved methods including; liaising with youth charities, spending time at sports groups, visiting travellers’ camps, volunteering at homeless centres and developing contacts with community elders. By seeking access to a range of hidden NEETs a sample was formed that consisted of; nine white working-class, six British-Pakistani, five homeless and four drug dealers. No specific ethnic/social group was targeted during the recruitment phase and the groups presented below emerged though initial analysis of the qualitative data. Each of these groups will be discussed in turn.

‘There are no unemployed people’

The first preliminary theme emerging from the research is that some young people are choosing not to claim welfare due to experiences or perceptions of the welfare state. Firstly, young men from British-Pakistani backgrounds appeared to have little or no knowledge of how the welfare state functioned, primarily due to other members of the community disengaging with the welfare state. Of those who had attempted to claim welfare in the past, they spoke of feeling demeaned and worthless because of the way in which they were spoken to. A constant theme was the perception of being made to feel stigmatized and ‘undeserving’ of support. Also, young men from this group viewed claiming welfare as a long-term alternative to employment – highlighting a widely held fear of falling into the ‘benefits trap’. In the absence of employment and welfare all young men from this group relied almost entirely upon their family for income, receiving free board and small amounts of money to fund inexpensive hobbies (such as football, online gaming and going to the gym).

Another distinct group emerging from the research was the homogeneity of experiences from white working-class men. Young men from this group frequently spoke of mental health being their key barrier to employment. Typically young men from this group were incredibly vulnerable to what they described as ‘bullying’ tactics from JCP staff to get them off benefits. These tactics included the threat of sanctions and mandatory training schemes if they failed to meet all of the requirements stipulated. The key challenge for most young men was being able to evidence that they were spending 30 hours per week searching for employment, as many did not have access to a PC at home, and in some circumstances the online tools were simply not conducive to finding work in their chosen sector (e.g. jobs as chefs are usually obtained through personally approaching the head chef). As a result of the perceived bullying and inflexible nature of the welfare regime all of the men in this group either chose to stop claiming or were sanctioned for not adhering to the strict procedures imposed by JCP. One young man explained that he lost his Employment Support Allowance after an assessment deemed him ‘fit for work’, simply because he was able to travel to the JCP alone. This left him unsupported and homeless, leading to an escalation of his existing depression, culminating in a suicide attempt.

As a result of not accessing benefits (either through choice or sanctions) five young men in the sample had become homeless. This distinct group appear to be similar to the white working-class group, albeit with fewer support networks, greater barriers to work and a higher instance of mental illness. All of the five interviewees in this group had also experienced psychotic symptoms (such as paranoia and hallucinations) due to smoking a former legal high called ‘Spice’. They too experienced what they deemed to be harassment and bulling from JCP staff, but were less able to deal with the ordeal associated with claiming benefits. In all, the young men in this group experienced the stigmatization of welfare and despite their highly precarious situations were ‘happier’ outside of the welfare system.

Finally, a group of young male drug dealers were also accessed via the research. All four young men in this group started selling small amounts of marijuana to their friends in order to fund their own consumption. As time progressed their desire to make more money than their peers and increasing their ‘social capital’ became strong motivators to become more entrenched in this world of low-level crime. One young man in this group had hopes to live a life without crime and enter the labour market, however, his criminal record held him back from getting a job and he was thus forced into claiming benefits. Due to perceived bullying and coercion at JCP he stopped claiming, ceased the search for work and returned to selling drugs to get by. Other young men in this group simply viewed claiming benefits as something that they could never do, as they did not want to be seen as a ‘scrounger’ by their peers. Despite enjoying the money that they earned (around £1,000 per month) they were acutely aware of the dangers associated with selling drugs – commonly speaking about friends who had ended up in jail and/or being victims of violence. A key motivator was the sense of entrepreneurship and the idea that they could make a lot of money and leave ‘the drug game’ to start their own legitimate business. Whilst this was their overriding aim, they did not know of any drug dealers who had successfully managed this transition.

These preliminary findings suggest that the current welfare system is not achieving the stated aim of ‘making work pay’ for many young men. Instead, the dual pronged approach of intensified conditionality and discursive stigmatization has resulted in some young people becoming distanced from the labour market.

Young People and Mental Health

(Chris Devany and Sadie Charlton)

Throughout my research, the poor mental health for young men in the study became a constant theme – ranging from occasional anxiety to more severe issues, including in one case a suicide attempt. All of the 24 participants to date spoke of their own mental health problems. Some groups appeared to be more vulnerable to experiencing symptoms on the severe end of the spectrum, specifically young men in the homeless and white-British groups. Negative interactions with JCP staff, poor social networks and sometimes traumatic experiences during childhood all appeared to play a role in causing and exacerbating these problems.

The increase in mental illness amongst young people in the UK is widely acknowledged, with welfare conditionality and sanctions seen as contributing factors (Powell et al, 2015). More broadly, research from Sweden has shown that “youth unemployment… is associated with increased risk of mental health problems” (Thern et al, 2017; 6). The issues around mental health and youth unemployment are not merely felt whilst they are outside of the labour market, but can persist into later life (Bell and Blanchflower, 2011) – this phenomenon is commonly referred to as ‘unemployment scarring’.

These points were developed by Sadie Charlton, an Occupational Therapist focussing upon youth mental health for a large voluntary sector organisation in Sheffield. She explained how the current treatment for young people with mental issues is fundamentally flawed, underpinned by deficit models that label some young people as ‘NEET’ or ‘with mental health problems’. She argued that these labels become a self-fulfilling prophecy and end up structuring young people’s lives. Instead, the her role focusses upon a holistic approach to boosting confidence, as opposed to more traditional models that merely treated the symptoms of mental illness.

Biography:

Chris Devany is a third year PhD student, Graduate Research Assistant and Associate Lecturer at the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield Hallam University.

Acknowledgements:

I would first like to acknowledge my co-organiser Abigail Woodward for organising the event with me and ensuring that it ran smoothly. Thank you to Beth Watts of Heriot–Watt University for inspiring me to write this blog and for her thoughtful suggestions.

I wish to highlight the support of PhD supervisors Richard Crisp and Tony Gore of CRESR for their encouragement throughout my research. Also, I want to extend my appreciation to Sadie Charlton, Nigel Brewster, our chair Adam Formby and all the attendees for taking time out of their busy schedules to contribute to the event.

Finally – thank you to the ESRC and the Sheffield Institute of Policy Studies at Sheffield Hallam University for making this possible.

References:

Beatty, C. and Fothergill, S. (2016a) Jobs, Welfare and Austerity: How the destruction of industrial Britain casts a shadow over present-day public finances. Sheffield: Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research. http://www4.shu.ac.uk/research/cresr/sites/shu.ac.uk/files/cresr30th-jobs-welfare-austerity.pdf

Bell, D. N., and Blanchflower, D. G. (2011). Young people and the Great Recession. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 27(2), 241-267

Crisp, R., and Powell, R. (2016). Young people and UK labour market policy: A critique of ‘employability’ as a tool for understanding youth unemployment. Urban studies, 54(8), 1784-1807.

Furlong, A. and Cartmel, F. (2007). Young people and social change: New perspectives. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

MacDonald, R., and Shildrick, T. (2007). Street corner society: leisure careers, youth (sub) culture and social exclusion. Leisure studies, 26(3), 339-355.

McDowell, L. (2002). Transitions to work: masculine identities, youth inequality and labour market change. Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, 9(1), 39-59.

McDowell, L. (2011). Redundant masculinities?: Employment change and white working class youth. London: John Wiley and Sons.

NOMIS (2017a). Claimant Count. London: Official Labour Market Statistics.

NOMIS (2017b). Labour Market Profile. London: Official Labour Market Statistics.

Office for National Statistics (2017). Contracts that do not guarantee a minimum number of hours: September 2017. London: Office for National Statistics.

Parliament. House of Commons (2017). Youth Unemployment Statistics. London: SN/SP/5871.

Powell, R., Bashir, N., Crisp, R. and Parr, S. (2015). Talent Match Case Study Theme Report; Mental health and wellbeing. Sheffield: Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research.

Thern, E., de Munter, J., Hemmingsson, T., and Rasmussen, F. (2017). Long-term effects of youth unemployment on mental health: does an economic crisis make a difference?. Epidemiol Community Health.

Unwin, J. (2016). Capital Ideas. In A Sense of Belonging (pp. 14-15). London: Fabian Society.