Hazel Dizon is a Masters candidate in Geography at York University in Toronto, Canada. In this blog, Hazel discusses her research on Occupy Bulacan – a housing takeover movement in the Philippines. Hazel received the Alan Holmans Award at this year’s HSA conference and her research has been published in the Radical Housing Journal which can be viewed here.

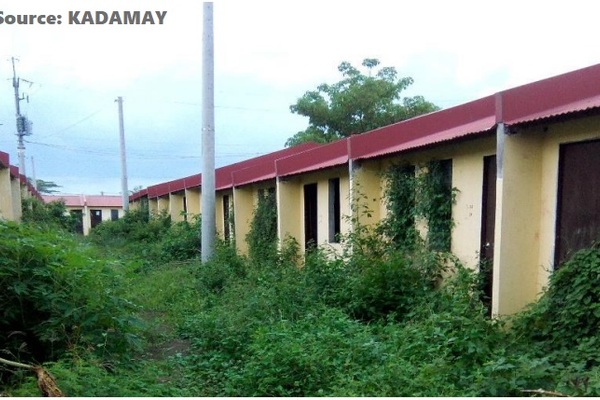

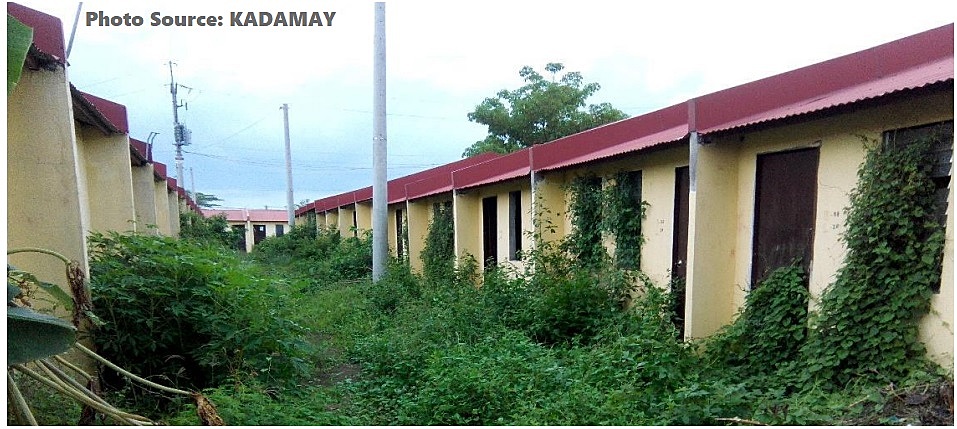

On 8 March 2017, 10,000 urban poor Filipinos marched to Pandi, Bulacan, an area immediately north of Manila, calling for their rights to housing. Dubbed Occupy Bulacan and led by the urban poor organization KADAMAY, the march culminated in the occupation of 5,300 empty and idled socialized housing units in the area – possibly the largest takeover of government-built housing in Asia. While the urban poor claimed victory against homelessness and market-based housing system, government officials and online commentators spewed out negative responses. The takeover was called ‘illegal’ and the ‘occupiers’ were called ‘thieves’, ‘anarchists’, ‘lazy’, ‘professional squatters’, etc. These reactions warrant further probing to pinpoint where the conflict is coming from and hopefully gain a sense of what should be done to achieve a socially just urban environment.

Taking inspiration from Ananya Roy’s (2005) perspective on urban informality, wherein the question of ‘to whom things belong’ can warrant multiple and contested answers, I looked into how social actors respond to the question of legitimacy of the occupation. Semi-structured interviews with the ‘occupiers’ and their leaders, government officials and housing officers, and the media, as well as social media posts from online commentators, provided statements that stand as their arguments. Invoking Henri Lefebvre’s Right to the City (1968/2000), I assessed the respondents’ statements on the legitimacy of the occupation between the contrast of right to appropriation and right to property and between use value and exchange value. Since the action of the urban poor was also a political manoeuvre, legitimacy is also deliberated between the tenets of democracy and right to participation.

Right to the City is Lefebvre’s call for an alternative world that is, as Purcell phrases it, “beyond capitalism, the state, and consumer society” (2014: 144). It is a right to an urban life that is less alienated, meaningful, more cognizant to the cycles and rhythms of life, open to conflicting and dialectical engagements; dominated by use value; and must be operating under the hegemony of the working class (Harvey, 2012; Lefebvre, 1968/2000: 179). This points to fundamental change and makes a case for the need to restructure power relations.

‘Right to appropriation’, the first component of right to the city, is the inhabitants’ claim to access, occupy, use, and produce the urban space. The homeless and the poor assert their claim to space because there is a move to exclude them due to their lack of property. Those excluded assert their right for appropriation, while those who are doing the exclusion are exercising their right to private property. This conflict is shown by the following interview statements where an occupier asserts his right to housing while an online commentator repudiates the occupiers who took over the houses without any form of payment:

“Housing is a right that should be given to people who are in need, isn’t it? Like us [whose house] have experienced flooding.” – Occupier 1

“There are those who are working hard to contribute towards their PAG-IBIG [government-owned and operated housing mutual fund], but you, KADAMAY members, just simply grabbed the houses. How lucky do you think you can get, you should work you’re lazy” – Panal, Instagram post, 2018

Space is a basic human need that should be available to all but has become an exclusive resource under capitalism through abstraction. While value (as socially necessary labour time) cannot be seen, it has been made “real” in social, economic, political, and cultural practice (Lefebvre, 1970/1991; Stanek, 2008). This concrete abstraction allows the existence of a commodity. In the case of space, its value has been layered with exchange value that is represented by a monetary equivalent. Over time, exchange value has come to dominate over use value. Even public housing has become inaccessible, as one of the occupiers experienced upon looking for financing options for it:

“My husband inquired if he could apply a loan from PAG-IBIG [government-owned and operated housing mutual fund] but was told he was ineligible. They said that his salary was not enough [to pay back the loan].” – Occupier 2

The ‘right to participation’, the second component of right to the city, urges inhabitants to take an active role in using and producing the city. The participation referred to here is beyond the liberal democracy and citizenship that we are conventionally familiar with. Democracy has a social contract attached to it – people give up some of their freedom in exchange for the state’s protection of their other rights (e.g. property rights). Their participation as citizens has been limited to voting, paying taxes, and following laws. The creation and the direction of the city, whether in terms of envisioning, planning, or physical structuring, is taken over by elected and appointed government officials and the business community.

Democracy, then, fortifies the hold of the ruled on private property. The state is given political legitimacy to manage spaces by establishing property laws and policies to protect the owners of private properties and assist the real estate sector in selling off land. Consequently, people critical of the occupation laid much emphasis on the legality and formal proceedings of acquiring property. This can be gleaned from the statement of a journalist:

“Even though it is true that the houses are better used than be left in deterioration, does that mean that they can just go there [take the houses] and abandon the process? Where’s the legal aspect of it all?” – Journalist 1

The freedom and liberty of property owners being protected by private property rights and the liberal market results in freedom to exclude, dispossess, and exploit inhabitants (Harvey, 2012). Occupy Bulacan, then, was a manifestation of a citizenship clash. The occupiers confronted the exploitative citizenship of the propertied with an alternative form of citizenship, which Holston (2009) calls insurgent citizenship. This does not indicate that the occupation was rebellious or espousing instrumental violence. In fact, the occupation was undertaken by an organized mass of people who, for months, underwent community consultations and dialogues with government institutions (Dizon, 2019). The occupation was the inhabitants’ way of practising democracy, participation, and citizenship.

The urban poor’s housing takeover was a highly contested move because it unsettled the neoliberal housing market by diluting the exchange value of property and it challenged elitist liberal democracy. In the process, the occupation activated the radical citizen, who challenged the entrenched and structured inequalities, and laid the ground for possible commoning of housing. This is the response of the occupiers to Lefebvre’s call for right to the city.

References:

Dizon, H. M. (2019). Philippine housing takeover. Radical Housing Journal, 1(1), 105-129.

Harvey, D. (2012). Rebel cities: From the right to the city to the urban revolution. London, UK: Verso Books.

Holston, J. (2009). Insurgent citizenship in an era of global urban peripheries: Insurgent citizenship in an era of global urban peripheries. City & Society, 21(2), 245–267.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Massachusetts: Wiley. (Original work published 1974).

Lefebvre, H. (2000). Writings on cities (E. Kofman & E. Lebas, Trans.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers. (Original work published 1968).

Panal, K. [@annepanal]. (2018, June 14). Dapat lang, sumusobra na, ung nagbabayad niyan sa

PAG-IBIG nagsusumikap para lang may pambayad [Instagram comment]. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/BkBrcrjF0cP/?taken-by=gmanews

Purcell, M. (2014). Possible worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the right to the city. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(1), 141–154.

Roy, A. (2005). Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 147–158.

Stanek, L. (2008). Space as concrete abstraction: Hegel, Marx, and modern urbanism in Henri

Lefebvre. In K. Goonewardena, S. Kipfer, R. Milgrom, & C. Schmid (Eds.), Space,

Difference, Everyday Life: Henri Lefebvre and Radical Politics (pp. 62–79).